- Home

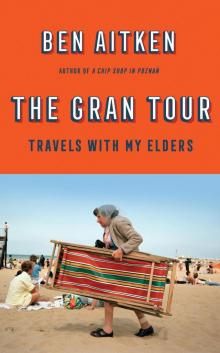

- Ben Aitken

The Gran Tour Page 7

The Gran Tour Read online

Page 7

‘No it’s not. You just want to steal a chip.’

‘Megan it’s effing Imelda.’

‘Oh yeah. Where’s Kieran?’

‘She looks lost.’

‘She looks happy.’

We go to the Tate gallery and join a free tour of the permanent exhibition with Andrew Jackson – a local retiree. AJ doesn’t hang around. Just about the first thing he says is: ‘The industrial revolution, coupled with the advent of photography, occasioned a splitting of painting. Its job of carefully representing this-and-that broke into a number of isms or styles. Consider this, for example …’ He shows us a Matisse, Notre-Dame, and says we’re to understand it as an example of Impressionism, which is to say the painting carries the ‘emotional investment’ of the artist. It’s what the artist saw, and how they felt, all in one, all mixed up. I like the sound of it. ‘The church is bathed in light,’ says Jackson, ‘but note the plume of smoke cutting across its bottom half. A warning, perhaps.’

We move along to Picasso’s Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle. ‘Picasso was a maverick,’ says Jackson. ‘He felt that the efforts made by painters to make things appear real and lifelike were tricks. Instead, Picasso shows that the canvas is flat, that paintings aren’t real. Here he has taken a conventional still life and broken it up and reassembled it madly. By breaking up the fruit bowl, he breaks convention, he breaks the fourth wall, and he brings the whole endeavour and practice of painting into question. He – and this painting – ask no less a question than: what is painting for?’

Andrew looks at us. We look back at him. Then he says that his last question wasn’t rhetorical, so does anyone have an answer? I look at Megan. She did History of Art for heaven’s sake. Surely she knows. They must have taught her what painting was for. Still, no one says anything. Andrew looks disappointed. He knew the 2008 recession had had some unfortunate effects but this, I think he feels, is taking the Michelangelo. He’s about to move on to the next room when a young girl, no more than seven, says, ‘Painting is for looking at.’ Andrew is quite taken by this remark. ‘Out of the mouths of babes,’ he says.

It isn’t the only thing the young girl has to say about art. She can’t believe Henry Moore got paid for doing ‘Two Forms’, and says she did something very similar to Mondrian’s Composition with Yellow, Blue and Red for her art homework and got an F. She did like Bryan Pearce and Alfred Wallis though, and so did I. Both Wallis and Pearce were so-called ‘naïve’ artists, meaning they hadn’t been trained, and didn’t bother with such bothersome things as scale and perspective. Jackson tells us that Wallis was ‘discovered’ by Ben Nicholson and Kit Wood when the two young Londoners popped down to Cornwall in the 1920s to check out the scene. They found Wallis buried under four tons of crabmeat round the back of a restaurant. ‘Gosh, blimey, Kit, look what we’ve discovered here. It’s a jolly old man. I wonder if he can paint.’

The two lads asked Wallis what he thought he was up to undiscovered beneath so much crab. Wallis, unsurprisingly, gave a somewhat crabby response. He said he was a retired mariner, thank you very much, and a widower to boot. He said he started painting when he was 67 after the death of his adoptive mother who he also had sex with. He said his conversion to painting wasn’t a bad redirection of purpose, all things considered, and a strong argument against what Anthony Trollope had in mind for anyone reaching the age of 67. He said he didn’t paint bowls of fruit or members of the nobility; nor did he paint pretty pastoral scenes or self-portraits; instead he painted what he remembered, and he did it without giving a second’s thought to technique, or precision, or verisimilitude, because he knew intuitively that it’s not how you paint that matters, but rather what you paint. Finally, he said that if he must be considered naïve, then it should be allowed that naivety can produce much better results than any amount of instruction or training.

There’s a danger of sounding patronising when praising the work of Wallis and Pearce – ‘Oh didn’t they do well given they had to use their toothbrush’ and so on. None of that. I loved Blue Ship (Wallis) and Monday (Pearce) for their honesty, their wit, their pathos, their warmth, and their defiance – witting or unwitting – of the status quo. Monday, for Pearce, is a humble domestic scene, is washing hanging out on the line, with the back door open and, I imagine, the radio on. I like that. I like that Monday. It might not have scale in the traditional sense, but it has scale in a worldly sense, for it reduces the world – or one seventh of it – to a simple, normal thing. It says: ‘This is what Monday is for me, and I make no bones about it.’ And his Three Pears is better than Picasso’s corrupted still life in my book. It shows three pears on a plate on a striped tablecloth. The brilliance and secret and genius of the painting (for me) is that one pear has fallen over, is on its side, has ignored the artist’s demand to ‘sit upright you silly pear!’ and has opted instead to lie down. The prone pear is a small act of subversion, and it makes the painting come alive.

Before we leave the gallery and head upstairs to the café for refreshment, a final word on Andrew Jackson. It’s not easy to bring paintings to life; to make sense of the abstract; to captivate children by somehow transforming Mondrian’s defection from realism into a dramatic act of treacherous brilliance. Because it’s not easy to do such things, it’s my feeling that Jackson should have his retirement interrupted and be despatched to Grimsby and Falkirk and Wrexham and Derry to whip up enthusiasm for Bacon and Wallis and Hepworth and Pearce; for painting, for art, for the creative act. Jackson is fluent and animated and inclusive. He’s a credit to the gallery, and to Cornwall. He should be framed and hung up. I’d certainly like to hear what he’d have to say about that.

We wander down to Porthmeor Beach and then up to what the locals call the ‘island’ – the green mound that sticks out into the sea. St Nicholas Chapel sits at the top. A sign says it’s possible to marry here. I’ve seen worse spots. Megan looks lovely next to the cold stone of the church. I choose my words carefully, then ask, ‘Would you like to get married here?’ A pause, and then: ‘Nah.’

Heading back to the hotel, we stop at the Sloop Inn for a quick drink. I have a half of Rattler cider, while Megan enjoys a pint of Sea Fury. It’s a pub with character. That’s what you’d say. Low ceilings, dark wood beams. All you need is a shoal of fishermen to burst in and promptly burst out in song – a shanty about all them pilchards that got away. Despite it being February, lots of people are sitting outside. They’re drawn to the sea. They’re watching the tide come in, watching it recover the bay. The sea is hitting the harbour walls, jumping up and rinsing children, who dance beneath the salty shrapnel.

I have another half and Megan another pint. She means business. If this carries on, by the end of the night Kieran will be saying to me, ‘Do you never drink, Ben?’, and Megan will be saying back, ‘We can’t afford for the two of us.’ So be it. If she’s going the way of Kieran, that’s fine by me. What isn’t fine by me is that she’s becoming a broken record. She keeps saying stuff like: ‘Such a good holiday, so therapeutic, can’t wait for tonight, love bingo, such a good holiday, not sure about pasties.’ When Megan says she wants a pint of Cornish Knocker (7.8 per cent abv) and she doesn’t care who knows it, I decide it’s time we made tracks to the hotel, and got some dinner in us.

We both start with chicken wings. Megan’s not saying much. I think she’s already hungover. She’s trying to construct something from the remains of her wings.

‘Are you alright?’ I say.

‘Who?’

‘You.’

‘Yeah, yeah. Need more wings.’

‘Hm. What are you working on there?’

‘Kieran and Imelda dancing.’

After a main of cassoulet and a pudding of panna cotta, we go through to the lounge. It’s second nature by now. Las Vegas could be outside and we wouldn’t give it a moment’s thought. We get a table between a fella called Michael Jackson (who won the bingo last night) and a fella in shorts. The fella in shorts hasn’t been out of them all we

ek, as far as I know. He’s dressed for a game of tennis, or to varnish the garden fence in summer. I’ve seen him about. You can’t miss him, really. Every evening he sits with his partner, they have a pint or two, and then she disappears. In her absence, he’ll have a few more pints and sit quietly on his own, tapping his foot to the music. Megan goes in for the bingo but I don’t bother. In the event, Michael Jackson wins the jackpot again. He tries to do a little moonwalk when he goes up for his prize.

Tonight’s entertainer is Gary K. He’s got his own portable signage. Megan’s in the loo. She’s been in there a while. When the dancing starts – ‘There Goes My First Love’ – Debra and Dawn appear out of nowhere and try and pull me up onto the dance floor. Dawn lets go of my arm when I say I’m not keen, but Debra – who’s had a bit of Sea Fury, I fancy – won’t take no for an answer. She’s got hold of my arm and is trying to yank me to my feet. It must make an odd scene for a neutral. In the end I’ve no choice but to yield. By now it’s ‘Locomotion’ and Gary K’s doing a good job of it. I’ve always loved the song, so make an effort to convey this with my body, but struggle to find a rhythm. Debra says I’ve got to behave like nobody was watching, which isn’t the most effective inducement because if nobody was watching I sure as hell wouldn’t be doing this. Debra’s nothing if not persistent. She’s grabbing my fingers now and shaking my arms around, as if I was an old car on a cold morning and this was how you got me going. I wish Meg was here. I could hide behind her. I try and copy Imelda. Do what she’s doing. Imelda says I should just shake it. I try to just shake it but something’s missing. I’m like a Hepworth sculpture – suggestive of life, but that’s about it. For some reason, Imelda and Debra and Dawn and Chris and Marie and some other ladies have put their handbags in a pile on the dance floor and are dancing around them and finding it hilarious. Chris is looking brilliant and feline in a black onesie. She’s turning heads all over the place, turning them all the way round in some cases. I get through ‘Locomotion’ and ‘Da Doo Ron Ron’ and then someone comes up and says, ‘I think your girlfriend’s been sick in the toilets.’

I put Megan to bed then return to the lounge and sit down next to the man in shorts – Mick. He says his wife goes up early because she gets tired and that he’s from Leicester, as if the one explained the other. He says he left school at twelve, got into construction, practically rebuilt post-war Leicester and then retired at 42, which was about 35 years ago. He’s one of thirteen children, but isn’t close to his siblings. ‘We were four in the same bed growing up. I reckon after that we just wanted the space. Having said that, the old man didn’t set the best example – in terms of closeness. I don’t remember him saying a single thing to me all my life. I used to do some rotten things just to get him to say something. I remember we were all on the bus and I pushed my brother off when it was going down Church Gate. All my father did was push me off ’n’ all.’

Mick’s 70-odd but hasn’t got a single grey hair. In fact it’s jet black, and clashes proudly with his chunky gold necklace. I ask if Mick lost his front teeth in a construction accident, or maybe when he got pushed off the bus that time, but it turns out he lost them in Skegness, when he was hit by a motorbike. He’s going back to Skeggy next week in his caravan, then Lowestoft the week after. He more or less lives in his caravan these days. Says you’ve got to keep moving, lest you get second thoughts. Before I get second thoughts, I ask him about the shorts. He admits he’s worn nothing else since he was 28. I ask him why. He gives it some thought, as if no one’s ever asked him before, then says, ‘I just find them easier to put on.’

There’s philosophy in that response. What kind of philosophy I can’t be sure, but there’s definitely philosophy.

16 Dawn might have had Ross Poldark in mind because he’s a local boy. At least, the Poldark stories are set mostly in Cornwall. They were a series of books initially, authored by Winston Graham. There was a telly adaptation in the 70s, and there’s another that’s ongoing. There was also an attempted adaptation by HTV in the 90s. HTV produced a pilot episode that didn’t go down well. Fifty members of the Poldark Appreciation Society picketed HTV’s headquarters in period costumes. No further episodes were made. I think it’s fair to say there can’t have been a lot going on in 1996.

8

Although owls appear zen and wise, they’re actually thick as sh*t

‘They’ve put you in a cage,’ says Megan, pointing to a cockatoo from Indonesia called Ben. (We’re at Paradise Park, a wildlife sanctuary six miles from St Ives.) Turns out that Ben the cockatoo is prone to self-harming: once he starts plucking his feathers, he just can’t get enough of it and will keep going until he’s practically starkers. Megan says that Ben is a message.

‘A message?’

‘A message to you.’

‘He’s not a message to me, Megan.’

‘Look Ben in the eyes and tell him he’s not a message.’

I look Ben in the eyes and tell him he’s not a message. Ben replies by starting to pluck his feathers. ‘See,’ says Megan.

The great grey owls are exceptionally mindful. They haven’t even a clue I’m here, gawping at them. They’re too busy focusing on their breathing, their feathers, their wings. I read that although owls appear zen and wise, and although they’re reputed to be sage and smart and so on, they’re actually thick as sh*t. And not as peaceful as they seem either. Great grey owls like nothing better than hunting small little lambs. They swoop and snatch them with their talons. Imagine the poor lamb, one second innocently nibbling grass, the next flying high above the Shropshire Levels, wondering what on God’s earth they’d done to deserve such a turn of events. I briefly imagine being similarly snatched by a swooping Kieran. ‘Now I’ve got yeh, yeh feckin’ wee eejit!’

The donkeys aren’t getting much attention. Nor are they getting much work these days. A sign explains that they’ve been unemployed since the EU imposed an eight-stone weight limit on their cargo. It is said the ass community can’t wait to take back control from Brussels so they can get some punters back in the saddle. Beyond the donkeys is a field of cauliflower. It’s lit by the sun, and in the distance across the River Hayle, over towards Lelant, I can see the train returning to St Ives. It’s a pleasant scene.

‘Why are you smiling?’ says Megan.

‘Hm?’

‘You’re smiling at the cauliflower.’

‘Am I?’

‘You didn’t smile at anything at the Tate.’

Mention of the Tate makes me wish Andrew Jackson was here to introduce me to all the birds and animals. I’d like to know his thoughts on the scarlet ibises. They’re lovely. Bright red plumage, long curved beak, and apparently they’ve a co-operative nature. A sign says that ‘juveniles start off a greyish colour and become scarlet as the birds mature.’ That’ll be right, I think, the gaining of colour with age; I’ve seen enough of that recently to believe in the idea. It’s when the sign goes on to say that ‘the birds nest in large breeding colonies’ that their symbolic appeal breaks down. Kieran appears at my shoulder. I say to him, ‘They don’t need cutlery with beaks like that,’ and he replies, ‘True, though I should like to see how they get on with a bowl of soup.’ Then Megan squeezes between us and says they’re pinky-red because they eat prawns. Kieran tells her not to be fecking ridiculous, but she insists it’s true. She says she once drank so much Ribena she turned purple, and I say, ‘And that’s why you think these birds are pinky-red, is it?’

The penguins are being fed. The spectacle is one of the park’s main attractions. Among the penguins is a solitary duck. Perhaps it identifies as a penguin. In any case, all eyes are on the penguins and the duck, which means that all eyes are not on the two seagulls perched above the action, on the summit of the rockery within the penguin enclosure. Their presence is hilarious. They’re desperate to pinch some of the penguins’ lunch but they also remember what happened last time. They keep turning to one another, just for a second, as if to say, ‘Shall we?’ D

espite being objectively far more diverting than the spectacle of twenty penguins eating sweetcorn, the seagulls are an unseen sideshow, seagulls being too common to summon our attention, unless, that is, they’re making off with our lunch. I think of Philip Larkin again. ‘Sun destroys the interest of what’s happening in the shade.’ A pair of shady seagulls indeed.

The best is saved to last – the chough. (Pronounced, I think, chuff.) It’s black apart from its beak and feet, which are red. It’s generally underwhelming, but with flashes of colour. More so than Ben the self-harming cockatoo, I can relate to the chough. Megan comes up to me and asks what’s wrong.

‘Nothing,’ I say.

‘But you’ve been staring at that bird for ages.’

‘Have I?’

‘It’s horrible, isn’t it?’

‘If you say so.’

‘What’s it called?’

‘A chough.’

‘Must eat a lot of Marmite.’

When we get back to the hotel, Megan goes to Barbara Hepworth’s studio and I go out for a longish walk, in order to get a sense of St Ives beyond its postcard streets down by the harbour. To risk stating the obvious, to know a thing requires familiarity with the whole of that thing. A sliver can give the wrong impression. If you only saw me for the first hour after waking, you’d conclude I was good for nothing but medical trials. So it is with places. We need to give them more room, more space, so they might make a fuller impression. A place is the sum of its parts, not some of its parts.

I cross the road and go down the steps to the beach. Because it’s half-term there’s a bucket-load of kids about. Freed of their education, the kids are currently behaving in ways that suggest they’ve never had any. The adults are little better, mind you. Here, a father has dug himself into a hole up to his neck. This undertaking was presumably done for the sake of his children, but they are nowhere to be seen, which is precisely where the father will be if he keeps this up. I’m not sure why, but I’d hazard the man’s an accountant.

The Gran Tour

The Gran Tour